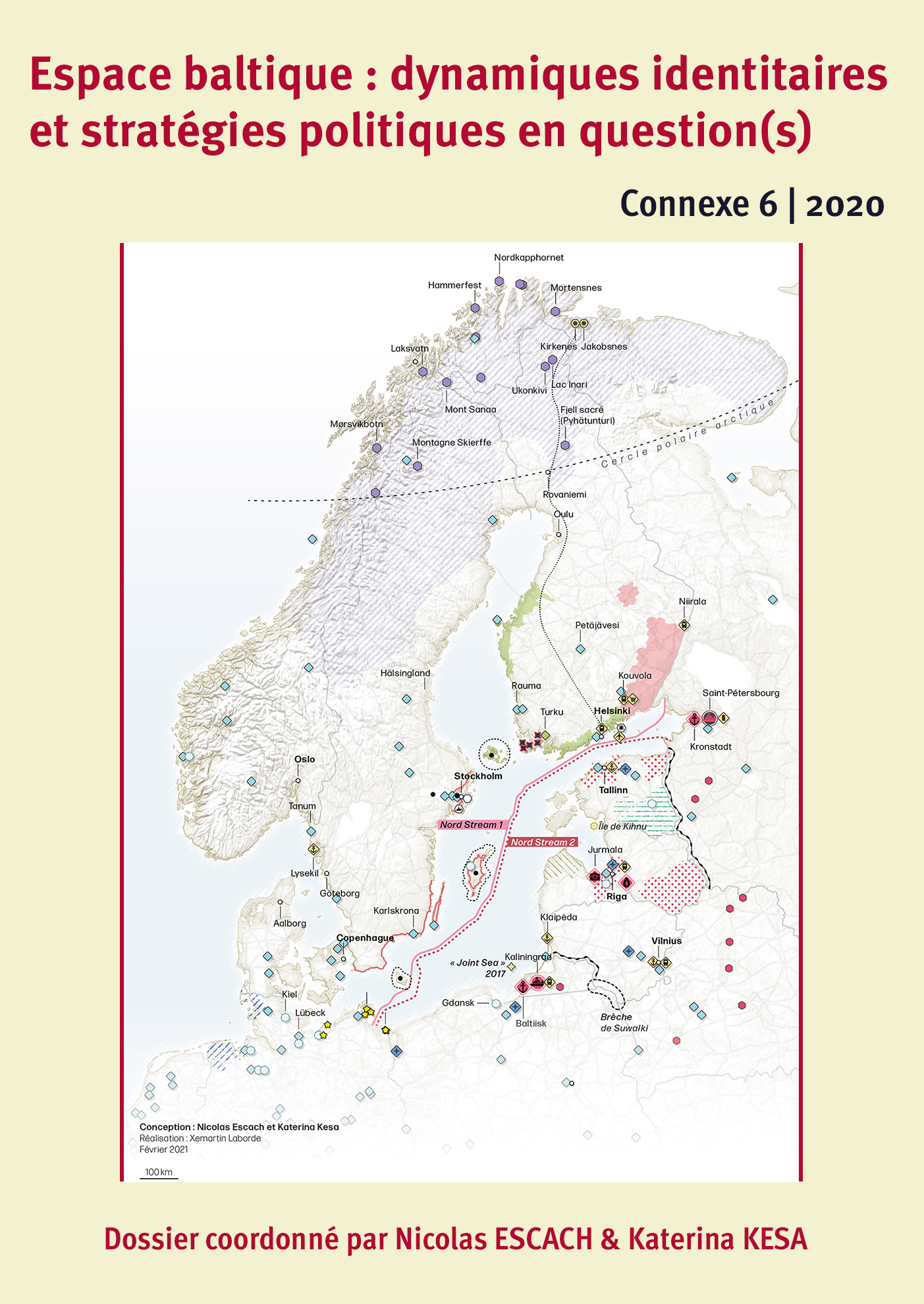

Circulation et transnationalisation de mouvements et idées populistes d’extrême droite dans l’espace baltique. Le cas du Parti populaire conservateur d’Estonie (EKRE)

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.5077/journals/connexe.2020.e355Keywords:

Baltic Sea region, circulation of practices, transnationalism, populism, Far-right, EKREAbstract

Populist Far-right movements have gained a lot of support in recent years. Their rise has come along with the emergence and increase of Far-right civic activism on the Internet. In Sweden, Finland, Estonia and Latvia, social networks have undoubtedly contributed to strengthening the appeal of populist Far-right movements, and has thus given them more visibility. Their political “tool” is to disseminate choking images or facts, often taken out of their original context. The dissemination of images and news through the media and social networks of Far-right movements against immigrants, the Other, in Finland and Sweden, together with their embracing in the Baltic countries are just examples of transnational circulation in the Baltic Sea region. While these images were used by ultraconservative actors in the Baltic States as political tools, the cases of Finland and especially of Sweden are portrayed by extreme right parties in Estonia and Latvia as “models not to follow.” Considering these factors, as well as the interactions which are numerous in the Baltic space, this article sheds light on a rather particular aspect of extreme right-wing populist movements by focusing on their transnational action and their networks in the Baltic space. By exploring the case of the Estonian Conservative Party (EKRE), this paper more generally seeks to demonstrate how certain far-right populist political ideas, perceptions and practices are conveyed or serve as an inspiration for others.

References

Auers, Daunis, and Andres Kasekamp. 2009. “Explaining the Electoral Failure of Extreme-Right Parties in Estonia and Latvia”. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 17 (2): 241–254.

Badie, Bertrand, et Dominique Vidal (dir.). 2019. Le retour des populismes. Paris : L’État du monde, La Découverte.

Braghiroli, Stefano, and Vassilis Petsinis. 2019. “Between party-systems and identity-politics: The populist and radical right in Estonia and Latvia”. 20 (4): 431–449.

Bickerton, Christopher. 2020. « Le peuple et les experts ». Esprit : comprendre le monde qui vient 61–62.

Bronnikova, Olga, et Katerina Kesa. 2019. « Perceptions et représentations de la Russie au sein du “monde russe” : Enquêtes dans les pays baltes et en France ». In La Russie dans le monde, éd. Anne de Tinguy, 249–278. Paris : CNRS éditions.

Commission européenne. Printemps 2019. Eurobaromètre Standard 91. « L’Opinion publique dans l’Union européenne ».

Coulet, Cyril. 2013. « La rhétorique de la blancheur dans les pays nordiques ». In De quelle couleurs sont les blancs ?, éd. Sylvie Laurent et al., 240–243. Paris : La Découverte.

Coulet, Cyril. 2018. « Taxinomie et effets de réseau parmi les droites extrêmes et populistes en Scandinavie ». Communication présentée à l’INALCO dans le cadre du séminaire du projet Espaces baltiques, le 18/11/208 (Centre de Recherches Europes-Eurasie).

Ekman, Mattias. 2018. “Anti-refugee Molibilization in Social Media: The Case of Soldiers of Odin”. Social Media + Society: 1–11.

Err.ee. 2018. “Helme: With enough defence capability, Estonia can ignore allies advice”.

Err.News. 2020. “Helme: Government is preparing a plan B in case NATO fails”.

Foreigner.fi. 2019. “Police investigates the xenophobic video that announces a ‘hunt’ of rapists”.

François, Stéphane. 28 novembre 2018. « Le populisme, un terme trompeur ». The Conversation.

François, Stéphane. 2019. « Les réseaux religieux de l’extrême droite. Un état des lieux ». Revue d’éthique et de théologie morale 303 : 89–107.

Ganesh, Bharath, and Caterina Froio. 2019. “The transnationalisation of far-right discourse on Twitter. Issues and actors that cross borders in Western European democracies”. European Societies 21 (4): 513–539.

Gomez-Reino, Margarita. 2018. Nationalisms in the European arena: Trajectories of transnational party coordination. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

Hatakka, Niko. 2016. “When logics of party politics and online activism collide: The populist Finns Party’s identity under negotiation”. New Media and Society 19 (12): 1–16.

Jakobson, Mari-Liis, Leif Kalev, and Saarts Tõnis. 2020. “Radical Right across borders. The Case of EKRE’s Finnish branch”. In Political parties abroad: A New Arena For Party Politics, ed. Tudi Kernalegenn and Emilie van Haute, 21–38. London: Routledge.

Johansson, Karl M. 2014. “The Emergence of Conservative Parties in the Baltic States: New Parties, Party Entrepreneurs and Transnational Influence”. In Models of Democracy in Nordic and Baltic Europe: Political Institutions and Discourse, ed. Nicholas Aylott, 77–115. London: Routledge.

Jungar, Ann-Cathrine. 2017. “Continuity and Convergence: Populism in Scandinavia”. In The Routledge Handbook of Scandinavian Politics, ed. Peter Nedergaard and Anders Wivel, 155–157. London: Routledge International Handbooks.

Kantar TNS Emor. 2020. “Erakondade reitingud 2020–2010”.

Kasekamp, Andres. 2015. “Fascism by Popular Initiative: The Rise and Fall of the Vaps Movement in Estonia”. Fascism. Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies 4 (2): 155–168.

Kasekamp, Andres, Mari-Liis Madisson, and Louis Wierenga. 2018. “Discursive Opportunities for the Estonian Populist Radical Right in a Digital Society”. Problems of Post-Communism 66 (1): 47–58.

Kesa, Katerina. 2015. « Pays récepteurs d’assistance étrangère et pays donneurs : la place et le rôle des États baltes entre pays nordiques et États postsoviétiques au prisme de l’action de parrainage (1985–2013) ». Thèse de doctorat. Université Sorbonne Paris Cité.

Kesa, Katerina. 2018. « Région de la mer Baltique, une “Méditerranée du Nord” ? ». Langues O’ Magazine. Le monde vu par l’Inalco : 34–36.

Kott, Matthew. 2016. “The far right in Latvia: Should we be worried?”.

Laruelle, Marlène, and Ellen Rivera. 2019. “Imagined Geographies of Central and Eastern Europe: The Concept of Intermarium”. IERES Occasional Papers: Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies. The George Washington University.

Lemieux, Vincent. 1999. Les réseaux d’acteurs sociaux. Paris : Presses Universitaires de France.

Mudde, Cas. 2007. Introduction to the populist radical right. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, Cas. 2013. “The 2012 Stein Rokkan Lecture. Three decades of populist radical right parties in Western Europe: So what?” European Journal of Political Research 52 (1): 1–19.

News now Finland. 2018. “Sweden’s Right Wing: More Finland, Less NATO”.

Objectif. Site Internet de Objektiiv.

Parlement estonien. 27 septembre 2016. Enregistrement du débat « Organisation du référendum à propos du plan de l’Union européenne concernant la répartition des immigrés » [Rahvahääletuse korraldamine Euroopa Liidu immigrantide ümberjaotamise kava osas].

Parlement européen. 2018. « Une Europe ouverte ».

Pilkington, Hilary, Elena Omelchenko, and Albina Garifzianova. 2010. Russia’s skinheads: Exploring and rethingking subcultural lives. London: Routledge.

Programme politique de EKRE. « Programme conservateur » [Konservatiivne programm].

Radvanyi, Jean (dir.). 2011 (3e édition). Les États postsoviétiques : Identités en construction, transformations politiques, trajectoires économiques. Paris : Armand Colin.

Silvennoinen, Oula, Marko Tikka, ja Aapo Roselius. 2016. Musta koidiku kuulutajad. Soome fašistide lugu [Les annonciateurs de l’aube noire. L’histoire des Fascistes finlandais]. Argokirjastus. Traduction du finnois vers l’estonien Suomalaiset fasistit. Mustan sarastuksen airuet. Helsinki: Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö (WSOY).

Stöcker, Lars Fredrik. 2017. Bridging the Baltic Sea: Networks of resistance and opposition during the Cold War era. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Torkaja. Site Internet.

Trumm, Siim. 2018. “The ‘new’ wave of populist right-wing parties in Central and Eastern Europe: Explaining electoral support for the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia”. Representation 54 (4): 331–347.

Uued Uudised. Site Internet de Uued Uudised [Nouvelles informations].

Vasilopoulou, Sofia. 2009. “Varieties of Euroscepticism: The Case of the European Extreme Right”. Journal of Contemporary European Research 5: 3–23.

Widfeldt, Anders. 2018. “The Growth of the Radical Right in Nordic Countries: Observations from the Past 20 Years”. Migration Policy Institute: 1–13.

Wierenga, Louis. 2017. “Russians, Refugees and Europeans: What shapes the ideology of the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia?”. Working Paper No. 6/2017. Tartu: Tartu University Press.

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

License

Some rights reserved 2021 Katerina Kesa

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.