Cosmopolitics and The Commons

|

Robert Farrow1 [0000-0002-7625-8396] 1 Institute of Educational Technology, The Open University (UK) Abstract. Who is open education for, and where might it ultimately lead us? This paper examines social and political dimensions of open education with a focus on the concept of cosmopolitanism and cosmopolitics. After providing an outline of open education, I proceed by critically examining the commonly held policy position that ‘publicly funded should mean openly licenced’, arguing that it implies a form of ‘weak’ moral cosmopolitanism. I describe ‘global citizenship’ and show its relevance to coordination in the efforts of open education through a commons supported by open licences. Tensions are surfaced between the universalist perspectives of cosmopolitanism and the recent emphasis on political issues such as social justice, decolonization, equity, diversity and inclusion in open education research. To address these, I explore a concept of openness as ‘counter-enclosure’ and argue for the relevance of a cosmopolitical perspective on open education. I draw on Leonelli’s (2023) distinction between openness as sharing and openness as judicious connection in the context of open science. I use this as the basis of a framework which describes a cosmopolitical perspective on open education. The discussion considers this framework in relation to recent developments in the commons: notably generative artificial intelligence which challenges long established notions of copyright and commoning. I suggest that positioning openness as an active practice of resisting privatisation - rather than merely a commitment to transparency or accessibility - open education functions as a site of political contestation rather than passive inclusion in neoliberal economies of knowledge. Keywords: Open education, OER, OEP, Cosmopolitanism, Cosmopolitics, The Commons, Artificial Intelligence |

1. Introduction: A Brief Overview of Open Education

“Open education” describes an inclusive range of pedagogical, technical and economic strategies which are directed towards expanding or enhancing pedagogical provision, educational equity, and the creation and sharing of knowledge. At the most fundamental level, open educators share an interest in widening participation in education, and extending opportunity to marginal, under-represented and disenfranchised populations. Infrastructurally, this ambition can be supported by promoting open access to educational materials, or through the use of open source software that lowers the costs associated with online and digital learning (Atenas et al., 2024).

Many open educators use and advocate for open educational resources (OER). OER are teaching and learning materials (of any format) that are either in the public domain or published on an open licence which permits various forms of redistribution, reuse and repurposing (UNESCO, n.d.; Hewlett Foundation, 2024; OER Commons, 2024). The most prominent examples of open licences are provided by Creative Commons (2019) and allow copyright holders to determine legitimate (re-)uses of their intellectual property. Creative Commons licences have been iterated and developed several times since their inception in 2002. They now claim a worldwide jurisdiction and align to the standards of open source software, facilitating legal and technical adoption (Hilton et al., 2020; Atenas et al., 2024). While critical takes on OER often point out the shortfall between the rhetoric of OER and what is delivered in reality (McDermott, 2020; Lee, 2020) studies have consistently shown that the satisfaction of learners, the quality of learning outcomes and the efficacy of OER are all consistent with proprietary resources (Hilton, 2020, Tlili et al., 2023).

While uptake of OER is unevenly distributed, many countries are seeing a dramatic change in open provision. The rise of the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) in the 2010s expanded provision to many, making it possible to take courses from highly reputed universities around the world for the cost of an internet connection and the time taken to study. MOOCs are open from the perspective of participation, but the contents of MOOCs are not necessarily openly licensed. This has given rise to debates around alternative definitions of ‘open’ and ‘openwashing’ in the education space (Stracke et al., 2019; Spector, 2017; Farrow, 2017). The growth in use and awareness of OER has taken place against a general background of digitalisation of learning materials, platformization, and innovation in pedagogical process which have often taken place with limited critical perspective (Decuypere et al., 2022; Teräs et al., 2020; Zhu, 2015).

Open Educational Practices (OEP) arguably came to prominence in the discourse around open education to clarify and authenticate practices endorsed by open educators (Uhlers, 2011). OEP may be understood in two ways (Cronin & MacLaren, 2018). Firstly, there are those behaviours associated with the use of OER, including OER-enabled pedagogy (Wiley & Hilton, 2018) and open pedagogy (Hegarty, 2015). Secondly, there are more expansive accounts of OEP which variously incorporate additional concepts such as networked learning (Weller, 2014;), critical digital pedagogy (DeRosa & Robison, 2017), facilitating social transformation (Smyth et al., 2016; Arinto et al., 2017), supporting equity, diversity and inclusion (Iniesto & Bossu, 2023), promoting social justice (Lambert, 2018; Hodgkinson-Williams & Trotter, 2018; Ossiannilsson, 2023; Karakaya & Karakaya, 2020; Clinton-Lisell et al., 2023) and decolonization (Adam, 2020; Khoo et al., 2020; Farrow et al., 2023). In recent years, this wider sense of OEP, which explicitly articulates goals which are socially and politically dimensioned, has become increasingly evident (Class et al., 2024). As these aspects become foregrounded, attention is being paid to the policies, strategies, theoretical foundation and ultimate goals of open education. Within this context, this paper aims to uncover and critically engage with the assumptions and implicit social and political commitments of open education.

2. Methods and Materials

This essay is based on a non-systematic review of literature taken from open education, theories of the commons, policy and strategy documents, philosophy, economics, anthropology and history. Sections 3.1-3.4 present an original normative argument and should be read sequentially as each builds on the previous section. The method of analysis is philosophical and reconstructive. Tensions between and within different philosophical positions are identified, explored and analysed, and the argument progresses through the attempt to dialectically resolve these. The overarching theoretical framework is practice-based immanent critique, which uses a rational reconstruction of observed norms and practical interactions to justify further claims grounded in this reconstruction (Stahl, 2021).

3. Results

3.1 1. Should Publicly Funded Mean Openly Licenced?

This section offers a thought experiment to analyse a pivotal policy that has been widely used by advocates of OER and OEP both prior and subsequent to the UNESCO (2019) Recommendation which sets out five areas for supporting uptake of OER: (i) building capacity of stakeholders to create, access, re-use, adapt and redistribute OER; (ii) developing supportive policy; (iii) encouraging inclusive and equitable quality OER; (iv) nurturing the creation of sustainable models for OER, and (v) facilitating international cooperation. The principles of open education as set out in The Cape Town Open Education Declaration (2007) advocate for open education policies which ensure that, where educational materials have been directly or indirectly funded by taxpayers, they should be made available on an open licence to ensure ongoing access (Campbell, 2020). D’Antoni and Savage (2009:138) similarly argued that “[r]esources created by educators and researchers should be open for anyone to use and reuse. Ultimately this argument resonates with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states: ‘Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages.’”

This commonly held position, which has been applied widely and brought about many policies in support of open education, can be summarised as “publicly funded means openly licenced” (hereafter “PFMOL”). The central premise is that taxpayers have a right to access what they have funded through government action. The weight of the argument is grounded in a kind of symmetry: since the public has funded these outputs, they also have a right to access them freely. Similar arguments have been successfully made with respect to non-educational materials, such as government documentation. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the Open Government Licence is routinely applied when publishing public sector information or reports (OGL, n.d.).

My strategy is to proceed by assuming that this argument is basically justified, and that members of the public have a right to the outputs of their state (exceptions such as data protection permitting). From this starting point we can develop a critical counter-argument. Consider that there are two countries: Country 1 and Country 2. Country 1 chooses to adopt PFMOL for the educational and cultural outputs that result from government funding. This means that citizens of country 1 are able to enjoy and share these outputs freely in the form of OER, cultural artefacts, etc. as well as the various services and practices which are offered as a result of access to these resources. Do the citizens of Country 2 have a right to access those cultural outputs which have been funded and shared by Country 1? Does it make sense that people from Country 2 should have a right to access the outputs of Country 1 when they do not contribute significant taxation to Country 1?

On the face of it, the answer

would seem to be ‘no’. In the context of PFMOL for a single country there

is a symmetry between the public funding of open educational resources (OER)

and the public consumption of those OER. This symmetry is compromised between

two or more polities which results in a less consistent position. The right of

citizens of Country 1 to access these materials is grounded in a claim to

access since their taxation is paying for the creation of the resources.

The people of Country 2 can make no such claim, since their taxation has not

paid for these materials. In essence, each country could function with

its own enclosed commons while consistently observing PFMOL. This symmetry is

lost when considering a comparison between two or more countries. Several

responses

to this ‘asymmetry’ objection are possible. These are summarised in Table

1.

Table 1. Possible responses to the ‘Asymmetry’ Objection to PFMOL.

|

Summary |

Description |

Comment |

|

National Commons |

Countries 1 and 2 limit access of their outputs to members of their own counties only.

|

Although arguably the most coherent rights-based response, this solution is impractical and not supported by current tools, licences and technologies. Neither country can benefit from the work of the other, and so both are poorer. This response is the least ‘open’ and in contradiction with the social mission of open education. |

|

Resist National Borders |

Treats national boundaries are artificial distinctions.

|

This does not work since national boundaries are a.) real in practical terms and b.) connote various relevant economic, legal, cultural and linguistic conditions. |

|

Unrestricted Knowledge |

Argues that any attempt to regulate the flow of knowledge in this way could not succeed in the digital age.

|

This may be true: in practice, it would be hard to limit a commons to a particular country. However, this does not address the normative elements of the Asymmetry objection. |

|

Mutual Recognition |

Countries 1 and 2 decide to mutually recognise the value of access to each other’s commons.

|

This deviates from the deontological premise of PFMOL, instead establishing a principle of acting from mutual self-interest. |

|

Global Commons |

Endorses the view that there is only one commons, and all cultural products should be there, regardless of which particular polity funded a particular output.

|

This effectively denies the separation between the commons of different countries. Many publics (as producers of content) can share one global commons. This is facilitated by how digital technologies reduce the cost and difficulty of sharing. Arguably this is the most common position adopted in practice. |

|

Cosmopolitanism |

Combines the ‘Global Commons’ response with a variation of ‘Resist National Borders’ (where national borders are real, but secondary).

|

The cosmopolitan position accepts the existence of national borders but takes them to be secondary to a primary commitment to world citizenship. |

Assuming that individual countries are duty bound to accept PFMOL for their own citizens, such duties do not extend to citizens of other countries. In the case of responding by appeal to a global commons the form of the argument changes. Instead of a deontological requirement, this position can be understood to appeal to a form of self-interest: all publics benefit from a healthy, high-quality, shared commons. Indeed, the ‘Shared Commons’ response is the closest to what really happens as a result of successfully implementing PFMOL. A deontological argument is used to first justify access to outputs by home citizens, and this is then extended through an appeal to consequentialist pragmatism (not specifically to rights or obligations). This argument begins from the position that the public have a right to outputs funded by their own taxes. From this, the argument can be made that everybody benefits from a universal commons, so it is in the ongoing self-interest of everybody in Countries 1 and 2 to support a global commons. The public domain challenges the idea that publics are separate - the public domain is supranational and universalised. This thought experiment shows that other attempts to resolve the tension result in the commodification of knowledge, supplanting a deontological claim with an argument from self-interest. Arguments from self-interest can be compelling, but it should be noted that interests change over time, and so arguments based in self-interest are inherently variable and contingent since circumstances, preferences and strategies can change .

An alternative resolution is provided by the cosmopolitan perspective. Cosmopolitanism states that individuals are first and foremost kosmopolitēs (“citizens of the world”). Cosmopolitanism conceptualises our social obligations as members of a world community rather than within the constraints of national, religious or cultural identity (though it makes provision for these). This is consistent with both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Cape Town Declaration. The nature of open licensing supports a global commons that is available for use across the world. Increasingly, educational initiatives work across international borders and invite us to reflect on the interconnected nature of the world after the invention of the Internet. Many open educators who contextualise their actions globally are already working within a global paradigm, and PFMOL is a policy formulation that reflects this. Open education often involves collaborative creation, modification, and distribution of educational resources among educators, researchers, and learners worldwide (Benkler & Nissenbaum, 2006). OER are created by individuals and institutions from various cultural backgrounds. Collaborative production encourages individuals from different regions and backgrounds to work together, exchange ideas, and co-create knowledge. By providing access to diverse perspectives, open education encourages learners to engage with different cultural, linguistic, and social viewpoints, supporting political cosmopolitanism. At the same time, many open educators are instead focused on solving local problems like providing textbooks or developing a curriculum. Their concern is not directed to a global commons. In the next section I develop a concept of ‘weak’ cosmopolitanism that can be applied to both.

This section has argued that PFMOL faces a logical objection based on the potential asymmetry between those that fund and those that consume open resources. Several possible responses were outlined, and I argued that the cosmopolitan response, which endorses both world citizenship and a global commons, is the most coherent resolution of the thought experiment, but also reflects implicit attitudes among many open educators who understand the potentially global impact of their work.

3.1 2. ‘Weak’ Cosmopolitanism in Open Education

“Cosmopolitanism is yet to come, something awaiting realisation” (Pollock at al., 2002:1)

In the previous section I developed a thought experiment based on the PFMOL policy and argued that a cosmopolitan (global citizenship) perspective, in conjunction with a global commons, can respond to the argument that one polity does not have the right to access the cultural outputs of another. In this section I argue that open education strategies align broadly through a global commons in what I term ‘weak’ cosmopolitanism. Cosmopolitanism is a contested concept, but one that has endured (Dardot & Laval, 2025). Cosmopolitanism is rooted in the philosophy that all human beings belong to a single community, emphasising moral and ethical responsibilities beyond national boundaries and citizenship. The interconnected nature of contemporary life and the open nature of internet infrastructure are facilitating the uptake of global and cosmopolitan perspectives (Beck, 2002). Globalisation is not static nor a linear process, and it is increasingly elaborated and altered by the interaction of national politics and international organisations.

The historical recurrence of cosmopolitan concepts may be understood as the solution to an ontogenetic problem. Human beings have a troubled history and prehistory. Survival has only been possible through sharing, cooperation and pooling of resources. Human beings are by nature and necessity social and, through language, communication and technology, benefit from the works, achievements and lessons of previous generations. The earliest forms of society are understood to have been nomadic, and organised around familial, tribal connections. Permanent settlements and societies developed alongside agriculture, allowing the first civilisations to develop. These processes largely occurred before historical recordings, but we do have many records of early civilisations and city-states (poleis/polis). This in turn provided a social centrality which, in the case of the ancient Greeks, also saw the first formal expressions of political power and control. It is within this historical context that the concept of cosmopolitanism first emerges courtesy of the arch-cynic philosopher Diogenes, who was well known to be a provocateur who rejected social authority. When he was asked where he came from (and despite being a citizen of Sinope) Diogenes replied, ‘I am a citizen of the world [kosmopolitês]’ (Diogenes Laertius, VI 63). This response is predicated on the split between the social and the natural, with Diogenes presumably asserting that one belongs first and foremost to the natural world of the cosmos rather than the constructed artifice of the polis. Cosmopolitanism thus understood is a response to local political power which gestures towards the general, natural and universal conditions of life.

Intellectual histories commonly trace (a simplified) genealogy of cosmopolitanism from Diogenes, through Socrates and the Stoics, to Kant and others thinkers of the European Enlightenment (Pollock et al., 2002; Rubiés, 2023). The revival of interest in cosmopolitanism in the 18th century took place alongside massive social change in Europe, catalysed by urbanisation, industrialisation, political revolution, and the upward thrust of capital. With the emergence of competing national, religious, economic and cultural identities, Cosmopolitanism was able to present itself as a way to theorise their synthesis into modern forms of identity. Enlightenment discourse attempted to find a rational basis for integrating competing traditions through appeal to an underlying common rationality and fundamental human rights, the same currents that would inspire revolutions in France and the Americas. Instead of the cynical form associated with Diogenes, Enlightenment cosmopolitanism tended towards utopian visions of an idealised and universal moral community.

The goal of Kant’s cosmopolitanism for instance, is thoroughly political: a united earth in which everyone is a citizen with their stake guaranteed by rights and representation (Kant, 1795; Kleingeld, 1998; Cavallar, 2012; Sanahuja, 2017). For Kant, the essential purpose of a cosmopolitan world government was to guarantee the laws supporting fair rights and representation. Theorists of cosmopolitanism do not agree on its final form. Some embrace a positive political vision in the form of supranational forms of political organisation like the United Nations or European Union (Zhang & Lillie, 2015). Alternatively, a strong philosophical tradition of moral (not political) universalism stemming from cosmopolitanism is associated with thinkers like Appiah (2006) and Nussbaum (1996). Cosmopolitanism accommodates these “norms of disengaged equivalence” (Calhoun, n.d.) by treating and valuing everyone equally as rational agents. Cosmopolitanism can thus be understood as a form of globalised liberalism, with multinational organisations reflecting the particular interests of nation states. (According to Rawlsian political theory, the nation state acts as a determinate form of the natural associations of mankind, providing the necessary forms of closure such as systems for politics and justice.) Rawls ultimately recommends a form of pluralism which can incorporate diversity as long as it does not disturb the basic contours of democracy: this is a classic liberal position, and echoes Popper’s (1945) paradox of intolerance. (For a fuller comparison of Rawlsian and cosmopolitan liberalism, see Tan, 2006; Reidy, 2013.)

Robust challenges to cosmopolitanism arise from marginalised experiences and struggles for recognition (Honneth, 1996), and these are frequently represented in open education through the lenses of equity, diversity and inclusion. Not all claims to recognition are equal, however. Should the claims to recognition made by, for instance, nationalist neo-Nazi groups, or fundamentalist religious cults be acknowledged and accommodated? In both cases, such groups openly advocate for the discriminatory treatment of others based on characteristics such as race and gender. Such groups fail to meet Popper’s criteria since they are insufficiently tolerant of difference. Thus, cosmopolitanism can celebrate diversity, equity and inclusion, but only up to a point (which is also true of liberalism). We might fairly conclude that cosmopolitanism contains inherent “contradictions of freedom and constraint, universality and particularity” (Fine & Smith, 2003).

In this paper I argue that open education is aligned with at least a weak cosmopolitanism. Weak cosmopolitanism is a form of moral cosmopolitanism, and does not include specific political dimensions or a requirement for a single set of laws regulating global activity (Miller, 2007; Knight, 2011). Essentially, this ‘weak’ form of cosmopolitanism equates to morally valuing all persons in the world. (A stronger form might include a requirement to act in such a way to promote equality between all peoples, or to ameliorate structural inequalities.)

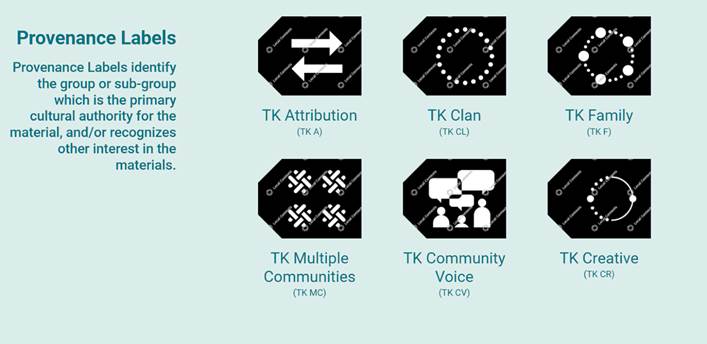

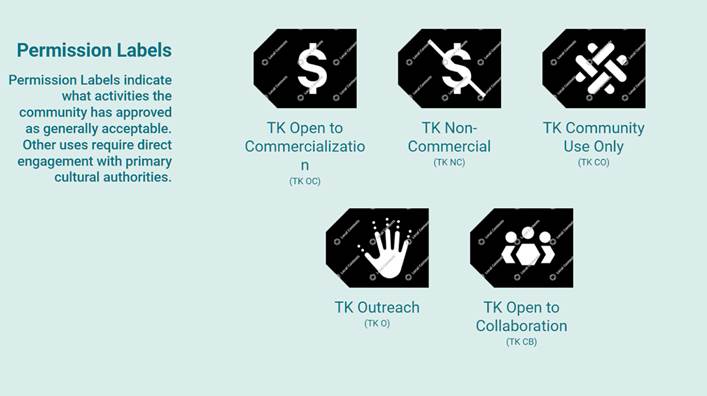

Of course, many open educators also act in support of stronger forms of cosmopolitanism, and some might deny that they are any sort of cosmopolitan. However, weak cosmopolitanism might be realised in many different ways (Pogge, 2008). In the example of open licences contributing towards a global commons, this may be understood as a moral duty rather than an action taken out of self-interest. The tension between universal and particular is evident in the recent emergence of traditional knowledge (TK) licensing. TK (n.d.) licences specify the ways in which indigenous knowledge and culture may be shared within and/or beyond relevant communities of origin. They are more granular than Creative Commons licences, and reflect a wider diversity of permissions and conditions for sharing. Figure 1 shows twenty examples of TK labels.

Fig. 1 Traditional Knowledge Labels (TK, n.d.)

TK labels offer greater specificity and control over indigenous knowledge, and can determine specific types of people or social roles that have access to particular pieces of information, or describe the social relationships that are appropriate for sharing. From the perspective of recognising the right of indigenous (or other communities) to share knowledge in particular ways, this is of course justifiable. In practice, TK licences are often added to Creative Commons licences as additional clauses. They provide additional specificity, emphasising particular and local considerations. TK licences are not focused on universal conditions for sharing, but instead reflect the context(s) from which they originate.

The emergence of TK licences disrupts the universalising tendency of open licensing. Open licences are directed towards a global commons, which, as I have argued above, can be understood as part of a cosmopolitan project. TK licences, while typically used in conjunction with open licences, also effectively limit their application. Undoubtedly this is appropriate and empowering, but what does this mean for the ambition of the commons, or for policy lines like PFMOL? Do we need to give up on the idea of a global commons because some knowledge cannot be shared without discrimination? In the following section I argue that we can overcome this dichotomy between universal and particular by conceptualising open education as a form of counter-enclosure.

3.1 3. The Cosmopolitical Commons: Open Education as Counter Enclosure

“Cosmos protects against the premature closure of politics, and politics against the premature closure of cosmos.” (Latour, 2004:454).

How can we theorise a commons which is directed towards the global good but also stops short of universalizing the norm that all knowledge should be shared openly? Perhaps ironically, there is no single shared understanding of the commons and several competing explanations and strategies for the commons (Bollier, 2024). Viewed historically, the commons is a locus for political and economic struggle. Papadimitropoulos (2017) identifies three main political theoretical approaches and their most influential thinkers: a liberal tradition which sees the commons as developing in conjunction with the state and markets (Ostrom, 2012, 2015; Benkler & Nissenbaum, 2006; Bollier, 2024); a reformist tradition which sees the commons as an alternative system of production and use of created works which emphasises peer collaboration and deemphasises profit motive (Bauwens & Kostakis, 2014; Arvidsson and Peitersen, 2016; Rushkoff, 2009) and an anti-capitalist tradition which understands the commons as an alternative (and point of resistance) to the appropriation of land, human being, intellectual property, knowledge, and culture by capital (Hardt and Negri, 2009, 2017; De Angelis, 2003, 2013; Caffentzis & Federici, 2014; Rigi, 2013; Meretz, 2012). It is therefore possible to theorise the commons anywhere along a spectrum from liberal acceptance to anti-capitalist resistance.

Depending on one’s theoretical orientation, the commons may thus present as an opportunity, or a problem that needs to be solved. Hardin (1968) first elaborated the idea of “the tragedy of the commons,” using the original concept of common grazing land. A self-interested shepherd might seek to increase the size of his flock to fill the available commons, but, if normalised by all shepherds, this can lead to overgrazing and the depletion of the commons. Thus, concludes Hardin, the commons requires regulation and some degree of private interest. Ostrum (2012) argues for a multi-valent, polycentric approach which strives to overcome Hardin’s public/private dichotomy. Notably, Hardin’s account predates the uptake of digital technology, and does not reflect the infinite resourcing of the digital (Nagle, 2018).

Hardin’s conceptualisation of the commons is one of finitude and limit. This makes sense with respect to the natural world, but less so with a digital world unconstrained temporally or spatially. However, capitalism has created artificial ‘enclosures’ and exclusionary property rights to the commons as a means of control and influence. The language of the commons has been appropriated by supra-national organisations like the World Bank and the United Nations as a strategy that reflects their market interests in both the physical and intellectual commons (Federici & Linebaugh, 2019). (Boyle (2008:45) claims that recent developments in intellectual property law amount to the “enclosure of the intangible commons of the mind.”)

In the digital age, the commons cannot practically be restricted to a particular country. Web 2.0 saw the development of a series of walled gardens as the tech giants attempted to create enclosures in cyberspace (Paterson, 2012). However, the interoperability of open standards, decentralised infrastructure, open governance standards, open cloud and data infrastructure have provided points of resistance to such control (Lombardi et al., 2021). Virtual private networks provide a convenient way to bypass any national restrictions on access (Harmening, 2025). Thus, the nature of the modern internet means that distinctions between digital commons are impractical to maintain.

Capitalism creates enclosures within what is by nature public and open: what was in the commons comes under private control. Standing (2019) has described how the process of “decommoning” is used to transform education into a private good where it benefits some more than others. The first step is enclosure and privatisation of public knowledge, following which we see state control of curriculum and the commodification of education systems, where every aspect of teaching and learning is treated as a commodity to be bought and sold. Despite the sheer abundance of available learning materials (Weller, 2011; Dyer-Witheford, 2007) artificial scarcity is introduced for digital learning materials like e-textbooks. Private equity extracts value from education by buying up assets, brands and services which make money, with the debt this creates typically being leveraged against learners.

With respect to open education, we see the full spectrum between liberal and anti-capitalist interpretations of the commons represented. For some companies, the commons is a potential source of profit where openly licensed content can be commercialised wherever the non-commercial clause is absent. For many advocates, open education represents a point of empowerment and resistance to neoliberal pressures on educational ecosystems. However, there is also a tendency within open education to restrict knowledge from the universal commons. The public domain is characterised by an absence of rights and claims from private interest or ownership. Typically, it includes works from before the instantiation of copyright or materials for which authorial copyrights have expired. Open licences assert private copyright and ownership with combinations of conditions (e.g. attribution; non-commercial use; no derivative works) to enable forms of universal public use. But how much “open” content meets the conditions for universal and permissive use when these conditions are applied? Only the public domain is truly a commons in this sense. The CC0 (n.d.) “No Rights Reserved” declaration offers a way for authors to unambiguously dedicate works to the public domain, but is not itself a licence - rather, it is a way to forgo all copyright claims automatically attributed to creators. Seen in contrast to the freedoms of the public domain, Creative Commons and TK licences are both offering nuanced control over the use and reuse of content.

There is a fundamental connection between openness and freedom. This theme cuts across the differing conceptions of the commons (liberal, reformist, anti-capitalist) though they modulate the way that freedom is defined or enacted (or what it might mean to be “open”). Open education can be understood to undermine the capture and enclosure of educational institutions by cultural and economic forces, and offers a reflexive mode of response to the attempt to privatise knowledge (Farrow, 2017; Peters & Deimann, 2013). This concept supports the universal commons which I have characterised as reflective of a moral cosmopolitanism. Open education broadly construed supports a concept of the commons which is unrestrained by enclosure, aligned with freedom and universal access to knowledge and creativity in a way that respects copyright protections (Neary & Winn, 2023). More ambitiously, the commons can be seen as a “parallel polis” which perpetuates peer-driven, socially oriented production in anticipation of a better future (as an alternative to transactional capitalism) (Bollier, 2024).

In the case of TK, the desire to control the dissemination and use of special knowledge needs to be understood as a post-colonial act. Colonialism is responsible for the capture and enclosure of many natural and intellectual commons, spuriously justified by the ‘savagery’ of native populations who had shown insufficient enthusiasm for exploiting themselves economically (Griffin, 2023; Greer, 2012). The ‘enclosure’ of these commons was a key part of the process of colonisation. Seen in this light, a reluctance to let those from outside an indigenous culture determine access, or to refuse to share sacred knowledge openly, should be seen not as an inconvenient disruption of the cosmopolitan tendency towards universalising access to knowledge, but as a different form of counter-enclosure. Characterising these different forms in this way allows us to preserve a common principle.

The underlying principle in both cases is to liberalise knowledge through the commons, but in a postcolonial context there is also a need to reassert control of something that has previously been ‘enclosed’ by others. TK licences by contrast may stipulate conditions of sharing which may be gender specific, or restricted to a particular clan (Fig. 1). One significant difference between Creative Commons and TK licences is that the former are difference-blind: one’s identity does not affect the permissions conveyed through the licence. Both forms of licensing mediate between humans and the public domain, towards an abstract universal cultural commons or a localised, connected community of practice. TK emphasises connection to the natural world, and frames enclosure accordingly. In this, it can be interpreted as part of what Hardt and Negri (2009) term the biopolitical commons of natural and technological environments as well as social factors such as knowledge and culture. Such a view centralises labour in social life and relates these to the production of forms of subjectivity: “the common” is understood not so much as an abstraction but rather as part of ourselves.

Hardin’s (1968) issues with scarcity in the commons still persist, of course, as far as the natural environment is concerned with the call for an effectively managed commons (Rose, 2020; Standing, 2019). There is therefore a need to understand the commons as not just digital intellectual property which exists in “the cloud” – what Dyer-Witheford (2007) terms “a commons of abundance, of non-rivalrous information goods” – but as part of the social lifeworld, part of nature and the wider ecosystem of human existence (Stevenson, 2018). Here the abstract universalism of cosmopolitanism can seem inattentive to particular contexts and cultures, whereas commoning can be understood as a form of political action (Bollier, 2024).

Arguably cosmopolitanism has always been challenged by the incorporation of political cultures which are not easily accommodated by its universal principles. How can we make sense of the commitment to social justice in light of cosmopolitanism? Is cosmopolitanism a form of social justice, or does it take away from the specificity and particularity of claims to social justice? In this section, I have argued that the tension between open education between moral universalism and particular political sensitivities is reflected in differing approaches to licensing and related to different conceptions of the commons. Seeing both as directed towards an objective of counter-enclose resolves any concept of competing maxims. However, be they digital, legal, practical, cultural, economic and so on, forms of enclosure are contextual and specific. This implies that, as counter enclosure, open education needs to be realised in a plurality of ways. Because it is premised on the idea that individual humans are the “primary units of moral concern,” (Pepper, 2016) moral cosmopolitanism struggles to accommodate the non-human as innately valuable. A holistic account of the commons, however, includes temporal, spatial, political, social, environmental and ecological factors, and so a theoretical perspective on open education should include these. In the next section, I suggest a concept of cosmopolitics that can facilitate this realignment for open educators.

3.1 4. Open Education as Cosmopolitics

“Never shall we pass from the closed society to the open society, from state to humanity, by mere broadening out. The two things are not of the same essence.” (Bergson, 1935:267)

This section develops a concept of cosmopolitics as a potential theoretical and political orientation for open educators. The term ‘cosmopolitics’ is associated with the work of Latour (2004a; 2004b) and Stengers (2010; 2011). Marx and Engels characterised 19th century cosmopolitanism as an ideological construct of capitalism, with markets and resources no longer constrained by the limits of the nation state. Latour (2004b) similarly accuses cosmopolitanism of a kind of ethnocentrism, arguing that globalisation was enthusiastically adopted for as long as it advanced the interests of the Global North (Leonelli, 2023:4). For Latour, we should conceptualise the world non-hierarchically, affording equal rights and value to human and non-human, natural and artificial environment, expert and non-expert knowledge, scientist and non-scientist. Rather than deferring political decisions to technical experts, Latour proposes a radical, discursive and inclusive democratic process.

Cosmopolitics proceeds from the basis that the Enlightenment vision of a cosmopolitan world is irredeemably destabilised by modernity. For the classic cosmopolitan, everybody is a global citizen whether they realise it or not. Under cosmopolitics, the task is instead to create a world where such a sense of citizenship is possible: “[c]osmopolitans may dream of the time when citizens of the world come to recognize that they all inhabit the same world, but cosmopolitics are up against a somewhat more daunting task: to see how this “same world” can be slowly composed (Latour, 2004b:457).” For Latour, the cosmopolitical perspective cannot find itself limited by the already existing commons, and must instead envisage alternatives (Latour, 2004a:461-2). The cosmopolitical is thus characterised by counter-enclosure, deconstruction and reconstruction.

“What cosmopolitics tries to describe is that ecologies are irreducibly complex societies of value-emitting organisms, technologies, and abiotic beings that are also centers of valuation. Technologies, no less than organic species, generate their own systems of values, constraints, and obligations that need tending to. Technologies, not unlike living beings, are never value-neutral, tools empty of their own content or characteristics. Technologies of all kinds—no matter what their use—are dynamic and lively agencies, bringing forth a series of unpredictable constraints, requirements, and possibilities that cannot be theorized in terms of their human usefulness alone.” (Robbert & Mickey, 2013:5-6)

Education has an important role in cosmopolitics as a route to the cultivation of critical exchange, building mutual understanding of different cultures (Stornaiuolo & Nichols, 2019). This can also be construed as a form of openness in both disposition and process. One goal for open education, therefore, can be to support the conditions under which such exchanges become feasible (Farrow et al., 2023). In Stenger’s work, “learning” is conceptualised as the activity of relating to and transforming the world in response to the artifices (fabrications, devices, ideologies, systems of value) created through human activity.

“[L]earning is never a process of remembering a truth that transcends the divergence of opinion. Rather, learning means hesitantly making sense, in common, of a situation that is made problematic due to the presence of artifices. These artifices elicit new ways of thinking, feeling, imagining, and responding, and acceding to a transindividual process of worldly transformation (Schildermans, 2023).”

As a theoretical orientation, cosmopolitics is grounded in poststructuralism, broadly oriented around the interrogation of systems of meaning and the institutions that perpetuate them. This has a potentially destructive/deconstructive connotation but can also be recognised as a liberatory exercise which opens up new possibilities for freedom and praxis. There are also affinities with posthumanism in the de-centring of “man,” emphasis on sociomateriality (Fenwick et al, 2011; Barad, 2007) and the emergent materiality of the digital (Kirchenbaum, 2012; Hayles, 2002). Cosmopolitical perspectives recognise the inherently political nature of education, its technologies and institutions. Cosmopolitics encapsulates the idea that political actions and policies should be informed by a sense of responsibility towards the entire human population, transcending national, cultural, and ethnic boundaries. This concept draws from the philosophical foundations of cosmopolitanism but also recognises “the entanglement of human and nonhuman practices and ethologies, the values and requirements wrought [by] technology, and the influential agency of the ecology of knowledge and ideas” (Robbert & Mickey, 2013:6). Here the cosmos indicates not “all people of the world” as in cosmopolitanism but the world as a whole, implying an anthropologically decentred world view balancing the human and non-human. Cosmopolitics is ontologically and epistemologically pluralistic, and scientifically reflexive: it acknowledges that practices are shaped by the world but also shape the world. Consequently, there can be no objective or metatheoretical position that can act as a universal or standpoint or organisational principle. Similarly, embodied practice is never value-neutral.

Critics of cosmopolitics accuse it of being unable to sufficiently account for difference and perpetuating a kind of liberal tolerance that maintains the status quo to the disadvantage of marginalised peoples (Watson, 2011). Stenger similarly criticises the liberal tradition of tolerance as fundamentally condescending. It seems appropriate to consider whether existing power relations can be changed through cosmopolitical actions, but as Fine (2011) argues, cosmopolitanism has always understood itself as an authentically emancipatory project, and this extends beyond any sense in which it is an ideological cover for the reproduction of Western values and interests. Notably, Kantian cosmopolitanism was expressly and originally framed as a critique of colonialism (Kautzer, 2013). The same can be said of the cosmopolitical project. Ultimately, the challenge of cosmopolitics is to radically revise our sense of the common, the “unenclosed” (Neary & Winn, 2023).

Endorsing the project of cosmopolitics has implications for open educators. Firstly, it is necessary to acknowledge that no-one’s practice is apolitical, or disconnected from the global. Instead, we should strive to reconcile local interests with global perspectives, emphasising the interconnected nature of educational ecosystems. The cosmopolitan goal of the global community, supported by appropriate governance and legal frameworks, remains central, but is tempered against a plurality of values. Secondly, it is important to foster collaboration between different kinds of experts (including non-experts) through inclusive discourse (which can be observed in activities like open pedagogy and other forms of OEP). Thirdly, there is an ongoing need to foster discussion and collaboration between the Global North and Global South, acknowledging historical injustices and present relations of power. The multivalence of privilege also necessitates attentiveness to the inequalities that exist within societies, and resistance to overly simple narratives or framings. Fourthly, the commons should be understood as a locus of political action and (potentially) social justice, with “counter-enclosure” being considered a guiding motif. Finally, cosmopolitics may offer a route to addressing some of the most pressing environmental, economic and political issues facing humanity - the so-called “wicked problems” (Rittel and Webber, 1973; Levin et al., 2012, United Nations, 2023). The intractability of issues surrounding climate change, public health, education and social injustices are characterised by transcending traditional, paradigmatic or disciplinary approaches and thus have no obvious or preferred solution, requiring collaboration and inquiry to approach.

Lenonelli (2023) has recently written about the central challenges of open science which align with the issues discussed in this paper. For Leonelli, the difficulties encountered in attempts to implement open science result from philosophical assumptions about scientific practice. She distinguishes two epistemic foundations for openness. Openness as sharing is focused around distributing scientific knowledge into the commons for the benefit of all society, relying on advanced digital technology infrastructures to support scientific practice. Leonelli argues that this is unlikely to realise the full potential benefits of open science since it furthers a single vision of what open science could be; and is overly focused on research output. Openness as sharing is oriented towards what we have discussed as a ‘weak’ moral cosmopolitan concern in open education: that we should extend the proposition of open education to every person, give them access to a universal commons, produce OER that is accessible to all, think globally, and so on. Openness as sharing is directed towards the commons in the most abstract sense. I suggest that it is aligned with the cosmos - the world in its totality - and the intended effect is for the free circulation of ideas supported by technical infrastructure. Leonelli (2023:7-8) acknowledges the value of such approaches, but argues that this form of sharing weakens epistemological diversity and prevents full realisation of the possible advantages of open science since transparency and access are insufficient by themselves and overlook the realities of existing iniquities.

By contrast, openness as judicious connection is embodied and performative, seeking connections between systems of practice while foregrounding agency, ethics and epistemic diversity in pursuit of scientific excellence: “[t]his understanding of openness emphasizes the dynamics of science as a human enterprise that brings different ways of acting and understanding the world in relation with each other, and thus fosters many different forms of output selection, organization and interpretation.” (Leonelli, 2023:8). Where openness as sharing places emphasis on scientific outputs which are treated as stable commodities which simply need to be distributed, openness as judicious connection concentrates on process, agency and relationality. This focus on systems of practice is fundamentally political in that it is concerned with localised, entrenched and demarcated sociocultural context.

I fundamentally support Leonelli’s position, which advances the conceptualisation of and debate around open science (particularly with regard to the strategic support for open science shown by many governance organisations). Leonelli does not focus on open education. However, when these distinctions are applied to open education, some constructive adjustments can be raised. The binarising of openness as sharing and openness as judicious connection may be too strict. OEP can be supported by a global commons of shared outputs. For OER to be translated or localised is only possible when a relevant resource already exists in a format that enables this. Publishing into a global commons may not be judicious, but can be a precondition for other, more strategically specific actions. Similarly, educational practices can support a global commons by fostering inclusive, participatory, and sustainable ways of sharing knowledge that transcend local and national boundaries while remaining sensitive to diverse contexts. Furthermore, this binary framing risks overlooking the possibility of a mediating perspective or actions that are more strategic. In this light, openness should not be conceived merely as a binary opposition but rather as an adaptive continuum that aligns shared, scalable outputs with locally grounded practices. Embracing a cosmopolitical stance, it becomes possible to recognise the mutual reinforcement of sharing and judicious connection. In practice, this means that contributing to a global commons can serve as an enabling condition for strategic, context-sensitive applications. Leonelli’s work primarily addresses the scientific research community and the structures that support it. The cosmopolitical perspective has a broader application, considering how openness operates across various societal domains and the global implications of knowledge sharing.

Table 2 appropriates and expands Leonelli’s (2023:65) “Synoptic comparison of the two interpretations of openness,” cross referencing a cosmopolitical interpretation which attempts to accommodate space for strategic action by conceptualising openness as counter-enclosure.

Table 2. Interpretations of cosmopolitical openness

|

Openness

as sharing |

Openness as counter-enclosure |

Openness as judicious connection |

|

Unlimited |

Strategic, scalable |

Relational |

|

Digital |

Platformed, entangled |

Social |

|

Good |

Negotiated |

Divisive |

|

Global |

‘Glocal,’ cross-culturally responsive |

Situated |

|

Equal |

Inclusive, negotiated |

Equitable |

|

Focused on itemized outputs (objects that can be shared) |

Relational structures (systems, governance, norms, values) |

Focused on social agency (ways of doing and being with others) |

Integrating the cosmopolitical concept onto Leonelli’s framework allows us to partially reconcile some of the tensions discussed so far in this paper. The cosmos aspect can be identified with the universal: inclusion, the commons, OER, accessibility, technical standards and global perspective. The political aspect is oriented instead towards activity, agency, local context, praxis, power, and practice (OEP). As part of this practice, critical perspective needs to be brought to the role of technology and the potentially exclusionary effects of sharing. Attention should be paid to the ways in which open education can contribute to bringing about a better world through both strategy and critical digital pedagogy. Thinking in terms of counter-enclosure provides a route to this (as we saw in the comparison between differing notions of the commons) but may also be realised differently in different (yet interconnected) contexts. Hence, “Open Data does not mean the sheer accumulation of research data on digital platforms, but rather the recognition that not all data can or should be made available, and choices need to be made and justified around which data are being shared, and how data infrastructures may support the creative exploration of such data” (Leonelli, 2023:8).

My contention here is that, for open educators, judicious connection should operate at a structural and strategic level. Rather than viewing openness as sharing and openness as judicious connection as opposing principles, it is therefore more useful to see them as points along a spectrum, where different contexts and needs call for different balances between broad dissemination and careful curation. Some initiatives may prioritise radical accessibility, making knowledge as widely available as possible, while others may emphasise ethical considerations, contextual relevance, or the protection of marginalised knowledge systems. These approaches need not be mutually exclusive. In practice, open education operates dynamically, adapting to shifting pedagogical, technological, and social conditions.

4. Conclusion: Cosmopolitics for Open Educators

I have argued that open education should be understood as a global project which is relevant to the whole of humanity. I characterised this as a form of cosmopolitanism or ‘world citizenship’ and argued that a common policy position for open education - namely, publicly funded means openly licensed’ (PFMOL) - implies a cosmopolitan position. From here, I developed a concept of ‘weak’ cosmopolitanism which is relevant to open education. ‘Weak’ cosmopolitanism is characterised by a universal moral interest in humanity, and evidenced by the global commons. I went on to recognise ongoing tensions around moral universalism in open education, using the example of Traditional Knowledge (TK) and its relation to the commons to explore this. Although I rejected the idea that cosmopolitanism presents a Eurocentric or colonial framework, I suggested that these tensions do require redress. I proposed a two-fold strategic approach. Firstly, that the commons be understood as the locus of counter-enclosure rather than dichotomised as either a universal, cosmopolitan interest or as a specific resourcing for a given community. This reframing led to a wider theoretical consideration about the relation between science, epistemology and politics. I argued that cosmopolitics (as distinct from cosmopolitanism) offers some advantages as an orientation for open educators and advocates as it attempts to balance global and local concerns. Table 2 provided a framework for open educators to reflect on their practice in relation to cosmopolitics.

In this paper, the social and political commitments of open education have been the focus. It was beyond the scope of this article to consider the unfolding and disruptive effects of generative AI on notions of the commons. However, in many ways this is the most pressing contemporary concern. The advent of these technologies introduces new complexities to the discourse on the commons in open education. AI providers have exhibited disregard for intellectual property rights, utilizing copyrighted content scraped from the internet to train language models. This practice raises concerns about the integrity and sustainability of the commons, as AI-generated materials, which are not currently copyrightable, effectively launder copyrighted content into the public domain. While we are seeing the emergence of guidelines on the use of AI in support of open education (e. g. Affordable Learning Georgia, n.d.) there is still great uncertainty about the long-term impact on the commons (Bozkurt et al., 2024).

Reconfiguring global and local knowledge systems through the commons is key to both cosmopolitical and decolonial ambitions. The main example of how cosmopolitics intersects with decolonial praxis discussed in this paper is TK licences. Cosmopolitics and decolonial praxis converge in their resistance to epistemic hegemony and their commitment to pluriversal futures. While cosmopolitics provides a framework for engaging multiple value systems without collapsing them into a singular order, decolonial praxis roots this engagement in historical experiences of injustice and the dismantling of colonial expressions of power. Cosmopolitics challenges the presumed neutrality of modern science, showing how it enacts power and excludes other knowledge systems. Decolonial praxis similarly critiques colonial science as a tool of domination and promotes epistemic justice by centring marginalised scientific traditions.

Currently, the nature of the commons is being redefined by decisions made in relation to extractive AI technologies, which mediate access to knowledge, automate decision-making, and reshape the conditions of participation in shared intellectual and cultural resources. While the digital commons have historically been built on principles of openness, transparency, and collective governance, AI introduces fresh asymmetries in power, control, and epistemic authority. The use of intellectual property to train large language models continues without regard for copyright or open licences. Algorithmic curation influences what knowledge is visible, while proprietary AI models challenge traditional understandings of communal ownership by appropriating intellectual properties and embedding these into public infrastructures. Cyberlibertarians have recently argued that all intellectual properties (regardless of licensing) should be available to all without compensation to their creators as a kind of fundamental human right (Justice & Golumbia, 2024:8). It is now common practice for all kinds of data to be used for such purposes without the knowledge or consent of creators nor those who the data might be about. In the absence of case law or adequate regulation, AI-driven platforms and data aggregators continue to appropriate intellectual and creative labour under the guise of openness, often reinforcing existing power imbalances rather than dismantling them. The widespread scraping of open-access materials, educational resources, and scientific datasets by corporate AI models exemplifies this issue, highlighting a growing tension between ideals of accessibility and the realities of extractive digital economies. AI-driven automation also raises questions about the sustainability of commons-based production, as tasks once reliant on human collaboration become outsourced to machine learning systems. These shifts necessitate an urgent re-evaluation of how the commons is structured, how it is interacted with, and what ethical visions should guide its evolution.

Similarly, Mirowski (2018) has criticized “open” science for presenting itself as increasing mass access to science while in fact promoting a form of platformed and extractive capitalism. This critique aligns with broader concerns about the logic of neoliberal value extraction and the resulting degradation of democracy (Brown, 2017), where open knowledge initiatives, while ostensibly democratising, often serve to consolidate control in the hands of a few dominant tech and publishing platforms. Rather than fostering true epistemic justice, these dynamics risk transforming the open movement into an instrument of dispossession, in which knowledge commons are enclosed, privatized, and monetized under the banner of openness.

This paper has elaborated how a concept of “open education as counter-enclosure” might provide a grounding which resolves some possible contradictions in the underlying maxims that guide the actions of open educators in diverse contexts. By positioning openness as an active practice of resisting privatisation, rather than merely a commitment to transparency or accessibility, open education can function as a site of political contestation rather than passive inclusion in neoliberal economies of knowledge. It should be noted, however, that we need not expect a cosmopolitical perspective to erase or resolve tensions between universal and particular. Rather, the value of cosmopolitics is in recognising, adapting to, and operating within such tensions, fostering a plurality of approaches that acknowledge competing epistemologies while resisting the totalising tendencies of dominant economic and technological forces.

Openness can be understood as a local concern, but, as argued in relation to “weak” cosmopolitanism, open education is inherently a strategic project with wider aspirations. A cosmopolitical approach to education is not just about including more voices; it is about reshaping education as a space of ongoing negotiation between different epistemologies, ontologies, and values. To engage in the project of open education is inherently political, since it is grounded in the idea that existing formal educational provision is in some way insufficient. Open educators anticipate a more equitable world, organised around access to learning and creativity. These utopian tendencies are important, but practice is necessarily grounded in the lifeworld. Cosmopolitics can provide a conceptual framing that keeps both aspects in view but is also an invitation to reflect on the political realities that inhibit the realisation of better worlds. As Neary & Winn (2012:420) put it, “[t]he question for a really open education is not the extent to which educational resource can be made freely available, within the current constraints of capitalist property law; but, rather, what should constitute the nature of wealth in a post capitalist society.” Undoubtedly this adds complexity to the project of open education while also raising possibilities to realise its transformative potential.

In this sense, the present study indicates several avenues for further research. I have focused on TK licences here to elaborate a cosmopolitical perspective which understands “open education as counter-enclosure”. Other constructs could be described and analysed empirically, including examples of regional adaptation of OER and attempts to decolonise curricula. Case studies could provide more granular descriptions of how cosmopolitics intersects with decolonial and emancipatory praxis in different contexts. This might include examinations of existing or possible policy; co-governance and consent models for institutions and assessment bodies; layered implementation models which include global and regional initiatives; pluriversal curriculum design; explorations of positionality and relational pedagogy; diversification of assessment; and investigations of the open education movement as a connected ecosystem of practice. Developing this empirical base would help open educators operationalise some of the commitments of a cosmopolitical perspective, and could provide a foundation for the development of policy.

5 References

Adam, T. (2020). Between Social Justice and Decolonisation: Exploring South African MOOC Designers’ Conceptualisations and Approaches to Addressing Injustices. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.557

Affordable Learning Georgia (n.d.). Guidelines for Using Generative AI Tools in Open Educational Resources. https://affordablelearninggeorgia.org/resources/opengenai

Appiah, K. A. (2006). Cosmopolitanism. Ethics in a World of Strangers. London: Penguin Books

Arinto, P. B., Hodgkinson-Williams, C., & Trotter, H. (2017). OER and OEP in the Global South: Implications and Recommendations for Social Inclusion. In C. Hodgkinson-Williams & P. B. Arinto (Eds.), Adoption and impact of OER in the Global South (pp. 577–592). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1043829

Arvidsson, A. & Peitersen, N. (2016). The Ethical Economy - Rebuilding Value After the Crisis. Columbia University Press

Atenas, J., Ebner, M., Ehlers, U.-D., Nascimbeni, F., & Schön, S. (2024). An Introduction to Open Educational Resources and Their Implementation in Higher Education Worldwide. Weizenbaum Journal of the Digital Society, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.34669/wi.wjds/4.4.3

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham and London: Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822388128

Bauwens, M., & Kostakis, V. (2014). From the Communism of Capital to Capital for the Commons: Towards an Open Co-operativism. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 12(1), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v12i1.561

Beck, U. (2002). The Cosmopolitan Society and Its Enemies. Theory, Culture & Society (Vol. 19, Issues 1–2, pp. 17–44). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327640201900101

Benkler Y. & Nissenbaum H. (2006). Commons-based Peer Production and Virtue. The Journal of Political Philosophy, Volume 14, Number 4, 394–419. https://nissenbaum.tech.cornell.edu/papers/Commons-Based%20Peer%20Production%20and%20Virtue_1.pdf

Berger, M. (2021). Bibliodiversity at the Centre: Decolonizing Open Access. Development and Change, 52: 383-404. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12634

Bergson, H. (1935). The Two Sources of Morality and Religion. Translated by Ashley Audra. New York: Doubleday. https://archive.org/details/twosourcesofmora033499mbp

Blaser, M. (2016). Is Another Cosmopolitics Possible? Cultural Anthropology. 31. 545-570. http://dx.doi.org/10.14506/ca31.4.05

Bollier, D. (2024). Challenges in Expanding the Commonsverse. International Journal of the Commons, 18(1), 288–301. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijc.1389

Boyle, J. (2008). The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind. Yale University Press. https://thepublicdomain.org/thepublicdomain1.pdf

Brabazon, T. and Lawrence, S. (2023). The claustropolitan society: A critical perspective on the impact of digital technologies and the lockdown imaginary. Fast Capitalism, 20 (1). pp. 86-99. https://doi.org/10.32855/fcapital.2023.006

Brincat, S. (2017). Cosmopolitan recognition: three vignettes. International Theory, 9(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971916000221

Brown, W. (2017). Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. Princeton University Press.

Bozkurt, A., Xiao, J., Farrow, R., Bai, J.Y.H., Nerantzi, C., Moore, S., Dron, J., Stracke, C.M., Singh, L., Crompton, H., Koutropoulos, A., Terentev, E., Pazurek, A., Nichols, M., Sidorkin, A.M., Costello, E., Watson, S., Mulligan, D., Honeychurch, S., Hodges, C.B., Sharples, M., Swindell, A., Frumin, I., Tlili, A., Slagter van Tryon, P.J., Bond, M., Bali, M., Leng, J., Zhang, K., Cukurova, M., Chiu, T.K.F., Lee, K., Hrastinski, S., Garcia, M.B., Sharma, R.C., Alexander, B., Zawacki-Richter, O., Huijser, H., Jandrić, P., Zheng, C., Shea, P., Duart, J.M., Themeli, C., Vorochkov, A., Sani-Bozkurt, S., Moore, R.L. and Asino, T.I. (2024). The Manifesto for Teaching and Learning in a Time of Generative AI: A Critical Collective Stance to Better Navigate the Future. Open Praxis, 16(4), 487–513. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.16.4.777

Caffentzis, G., & Federici, S. (2014). Commons against and beyond capitalism. Community Development Journal, 49(suppl 1), i92–i105. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsu006

Calhoun, C. (n.d.). Cosmopolitanism, nationalism, and belonging (Project Description). https://calhoun.faculty.asu.edu/projects/cosmopolitanism-nationalism-and-belonging

Calhoun, C. (2012). Cosmopolitan Liberalism and Its Limits. In: Robertson, R., Krossa, A.S. (eds) European Cosmopolitanism in Question. Europe in a Global Context. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230360280_7

Campbell, L. M. (2020). The Soul of Liberty: Openness, equality and co-creation. In Bali, M., Cronin, C., Czerniewicz, L., DeRosa, R., & Jhangiani, R. S. (Eds.), Open at the Margins (pp. 198 – 209). Rebus Community. https://press.rebus.community/openatthemargins/

Cavallar, G. (2012). Cosmopolitanisms in Kant's philosophy. Ethics & Global Politics, 5:2, 95-118, . https://doi.org/10.3402/egp.v5i2.14924

CC0 (n.d.). CC0. https://creativecommons.org/public-domain/cc0/

Chase-Dunn, C. and Mann, K. M. (1998). The Wintu and Their Neighbours: A Very Small World-System in Northern Carolina. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Class, B., Bebbouchi, D., Fedorova, A., Cheniti, L., El Khayat, G., & Shlaka, S. (2024). Towards a Competence Framework for Open Scholars: Acknowledging the Dearth of Epistemic Competences. Open Praxis, 16(3), 326–346. https://doi.org/10.55982/openpraxis.16.3.672

Clinton-Lisell, V. E., Roberts-Crews, J., & Gwozdz, L. (2023). SCOPE of Open Education: A New Framework for Research. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 24(4), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v24i4.7356

Creative Commons (2019). About CC Licences. https://creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/

Cronin, C., & MacLaren, I. (2018). Conceptualising OEP: A review of theoretical and empirical literature in open educational practices. Open Praxis, 10(2), 127–143. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.559671315718016

D’Antoni, S., & Savage, C. (2009). Open educational resources: conversations in cyberspace. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000181682

Dardot, P., & Laval, C. (2025). Instituer les mondes: Pour une cosmopolitique des communs. La Decouverte.

De Angelis, M. (2003). Reflections on alternatives, commons and communities. The Commoner, 6 (Winter), 1-14. https://files.libcom.org/files/1_deangelis06.pdf

De Angelis, M. (2013). Does capital need a commons fix? ephemera, 13(3), 603. https://ephemerajournal.org/sites/default/files/2022-01/13-3deangelis.pdf

DeRosa, R., & Robison, S. (2017). From OER to open pedagogy: Harnessing the power of open. InR. S. Jhangiani & R. Biswas-Diener (Eds.), Open: The philosophy and practices that are revolu-tionizing education and science. London: Ubiquity Press. https://doi.org/10.5334/bbc

Decuypere, M., Grimaldi, E., & Landri, P. (2021). Introduction: Critical studies of digital education platforms . Critical Studies in Education, 62(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2020.1866050

Diogenes Laertius (1925). Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, R.D. Hicks (trans.), vol. 2, (Loeb Classical Library 184), Harvard: Harvard University Press, pp. 3–109. https://archive.org/details/DiogenesLaertius01LivesOfEminentPhilosophers15_201412/mode/2up

Disco, N. and Kranakis, E. (2013) (eds.). Cosmopolitan Commons: Sharing Resources and Risks across Borders. MIT Press. https://direct.mit.edu/books/edited-volume/3717/Cosmopolitan-CommonsSharing-Resources-and-Risks

Ehlers, U.-D. (2011). Extending the territory: From open educational resources to open educational practices. Journal of Open Flexible and Distance Learning, 15(2), 1–10. http://www.jofdl.nz/index.php/JOFDL/index

Eskow, R. (2024). The Only Ethical Model for AI is Socialism. Current Affairs (July). https://www.currentaffairs.org/news/the-only-ethical-model-for-ai-is-socialism

Farrow, R. (2017). Open education and critical pedagogy. Learning, Media and Technology 42 (2): 130-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2016.1113991

Farrow, R., Coughlan, T., Goshtasbpour, F., & Pitt, B. (2023). Supported Open Learning and Decoloniality: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1115. MDPI AG. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111115

Federici, S., & Linebaugh, P. (2019). Re-enchanting the world: feminism and the politics of the commons. PM Press / Kairos

Fine, R. (2011). Enlightenment Cosmopolitanism: Western or Universal? In: Adams D., Tihanov, G. (eds.) Enlightenment Cosmopolitanism. Oxford: Legenda, 153–169.

Fine, R. and Smith, W. (2003). Jürgen Habermas’s Theory of Cosmopolitanism. Constellations Volume 10, No 4. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1351-0487.2003.00348.x

Flores Silva, F. (2022). Cosmopolitanism, cosmopolitics and indigenous peoples: elements for a possible alliance. Alternautas, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.31273/alternautas.v4i1.1051

Greer, A. (2012). Commons and Enclosure in the Colonization of North America. The American Historical Review, Volume 117, Issue 2, 365–386, https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.117.2.365

Griffin, C. J. (2023). Enclosure as Internal Colonisation: The Subaltern Commoner, Terra Nullius and the Settling of England’s ‘Wastes.’ Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 1, 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0080440123000014

Hall, G. (2023). Experimenting with Copyright Licences. Copim. https://copim.pubpub.org/pub/combinatorial-books-documentation-copyright-licences-post6

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 162,1243-1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Hardt, M. & Negri, A. (2009). Commonwealth. Cumberland: Belknap Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjsf48h

Hardt, M. & Negri, A. (2017). Assembly. Oxford University Press.

Harmening, J. (2025). Virtual Private Networks. In Computer and Information Security Handbook (pp. 979–992). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-443-13223-0.00059-x

Hayles, N. Katherine (2002). Writing Machines. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hegarty, B. (2015). Attributes of open pedagogy: A model for using open educational resources. Educational Technology, 3–14. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44430383

Hewlett Foundation (2024). Open Education. https://hewlett.org/strategy/open-education/

Hilton, J., III. (2020). Open educational resources, student efficacy, and user perceptions: A synthesis of research published between 2015 and 2018. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 853–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09700-4

Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science 162: 1243-1248. https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

Hodgkinson-Williams, C. A. & Trotter, H. (2018). A Social Justice Framework for Understanding Open Educational Resources and Practices in the Global South. Journal of Learning for Development, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v5i3.312

Honneth, A. (1996). The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. MIT Press.

Iniesto, F., & Bossu, C. (2023). Equity, diversity, and inclusion in open education: A systematic literature review. Distance Education, 44(4), 694–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2023.2267472

Justice, G., & Golumbia, D. (2024). Cyberlibertarianism: The right-wing politics of digital technology. University of Minnesota Press.

Kant, I. (1795). Toward Perpetual Peace. In Kant: Political Writings, 2nd. ed., H Reiss (Ed), Cambridge University Press.

Karakaya, K., & Karakaya, O. (2020). Framing the Role of English in OER from a Social Justice Perspective: A Critical Lens on the (Dis)empowerment of Non-English Speaking Communities. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(2), 175-190. Retrieved from https://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/508

Kautzer, C. (2013). Kant, Perpetual Peace, and the Colonial Origins of Modern Subjectivity. peace studies journal 6 (2):58-67. https://peacestudiesjournal.org/volume-6-issue-2-2013/

Kirchenbaum, M. (2012). Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. MIT Press. https://direct.mit.edu/books/monograph/3356/MechanismsNew-Media-and-the-Forensic-Imagination

Khoo, S.-M., Mucha, W, Pesch, C. and Wielenga, C. (2020). Epistemic (in)justice and decolonisation in higher education: experiences of a cross site teaching project. Acta Academica, 52(1), 54-75. https://dx.doi.org/10.18820/24150479/aa52i1/sp4

Kleingeld, P. (1998). Kant’s Cosmopolitan Law: World Citizenship for a Global Order. Kantian Review, 2, 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1369415400000200

Knight, C. (2011). In Defence of Cosmopolitanism. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 58(129), 19–34. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41802517

Latour, B. (2004a). Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (2004b). Whose Cosmos, Which Cosmopolitics? Comments on the Peace Terms of Ulrich Beck. Common Knowledge 1 August 2004; 10 (3): 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1215/0961754X-10-3-450

Lambert, S. R. (2018). Changing our (Dis)Course: A Distinctive Social Justice Aligned Definition of Open Education. Journal of Learning for Development, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v5i3.290

Lee, K. (2020). Who opens online distance education, to whom, and for what? Distance Education, 41(2), 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1757404

Leonelli, S. (2023). Philosophy of Open Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009416368

Levin, K., Cashore, B., Bernstein, B. and Auld, G. (2012). Overcoming the Tragedy of Super Wicked Problems: Constraining Our Future Selves to Ameliorate Global Climate Change. Policy Sciences, 45, 123-152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-012-9151-0

Lombardi, M., Pascale, F., & Santaniello, D. (2021). Internet of Things: A General Overview between Architectures, Protocols and Applications. Information, 12(2), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12020087

Marx, K. (1867). Capital: A critique of political economy. Volume 1, Part 1: The process of capitalist production. New York, NY: Cosimo. https://archive.org/details/capitalcritiqueo01marx/page/n5/mode/2up

Mauss, M. (1954)[2002]. The Gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies. Routledge: London and New York. https://ia800306.us.archive.org/18/items/giftformsfunctio00maus/giftformsfunctio00maus.pdf

McDermott, I. (2020). Open to what? A critical evaluation of OER efficacy studies. In the Library with the Lead Pipe. https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2020/open-towhat/

Meretz, S. (2012). The structural communality of the commons. In D. Bollier & S. Helfrich (Eds.), The wealth of the commons (pp. 28–44). Amherst, MA: Levellers Press. https://wealthofthecommons.org/essay/structural-communality-commons

Michael Spector, J. (2017). A Critical Look at MOOCs. In: Jemni, M., Kinshuk, Khribi, M. (eds) Open Education: from OERs to MOOCs. Lecture Notes in Educational Technology. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-52925-6_7